In October 2024, following a publication of an article in the Journal of Field Archaeology, a small, unassuming piece of purple fabric uncovered in an ancient tomb in Vergina captured worldwide attention. Thought to have once belonged to Alexander the Great (356-323 BC), this tunic fragment—described as a sacred “sarapis”—has sparked fresh debate among historians and archaeologists alike. If authenticated, this tunic might provide an unprecedented glimpse into Alexander’s personal life, rituals, and even his adoption of Persian customs. However, the claims are not without controversy, and questions remain as to whether the tunic indeed belonged to Alexander.

Here, we explore the significance of this discovery, what it could reveal about Alexander the Great, and how it contributes to our understanding of his historical legacy.

The elegant Doric-style façade of Tomb II at Aigai (Vergina), traditionally attributed to Philip II, with its fresco of a royal hunting scene (4th c. BC).

The elegant Doric-style façade of Tomb II at Aigai (Vergina), traditionally attributed to Philip II, with its fresco of a royal hunting scene (4th c. BC). © Teresa Otto / Shutterstock

The elegant Doric-style façade of Tomb II at Aigai (Vergina), traditionally attributed to Philip II, with its fresco of a royal hunting scene (4th c. BC).© Teresa Otto / Shutterstock

The golden larnax, containing the cremated remains of perhaps Philip II, from Tomb II at Vergina (Museum of the Royal Tombs at Aigai).

The golden larnax, containing the cremated remains of perhaps Philip II, from Tomb II at Vergina (Museum of the Royal Tombs at Aigai). © Arnaoutis Christos / Shutterstock

The golden larnax, containing the cremated remains of perhaps Philip II, from Tomb II at Vergina (Museum of the Royal Tombs at Aigai).© Arnaoutis Christos / Shutterstock

A Tunic Fit for a King?

Professor Antonis Bartsiokas and his team from Democritus University of Thrace have identified a fragment of “inconspicuous material” in the golden ossuary, or “larnax,” found within the main chamber of Vergina’s Tomb II. Discovered in 1977, this tomb complex has long been associated with the Macedonian royal family, particularly Alexander’s relatives, including his infamous father, Philip II of Macedon (382-336 BC), and his half-brother, Philip III Arrhidaeus (357-317 BC). Yet, no artifact had ever been definitively linked to Alexander himself—until now.

The fragment, which Bartsiokas’s team believes could have been part of Alexander’s royal chiton—a tunic-like garment made from a single cut of cloth—has revived debates surrounding the tomb’s occupants. This tomb, part of the burial grounds of the Argead (Temenid) dynasty—Alexander’s ruling family—is considered the final resting place for some of ancient Macedonia’s most powerful figures. Notably, Bartsiokas’s findings focus on the unique composition and history of this garment, possibly offering a direct link to Alexander’s conquests.

The Great Tumulus of Aigai (Vergina), the royal burial mound of the Argead (Temenid) dynasty. The entrance can be seen to the right.

The Great Tumulus of Aigai (Vergina), the royal burial mound of the Argead (Temenid) dynasty. The entrance can be seen to the right.

The Great Tumulus of Aigai (Vergina), the royal burial mound of the Argead (Temenid) dynasty. The entrance can be seen to the right.

The Great Tumulus of Aigai (Vergina), the royal burial mound of the Argead (Temenid) dynasty. The entrance can be seen to the right.

A Persian Garment in a Macedonian Tomb

According to Bartsiokas, the tunic was crafted from cotton, a material rarely seen in Macedonia at the time but more common in Persia, where Alexander campaigned extensively. Using non-destructive analysis techniques, such as optical microscopy and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy, researchers determined that the fabric’s materials align with ancient descriptions of garments linked to Alexander, including references to a special purple dye known as Tyrian purple. This rare dye, painstakingly extracted from sea snails, was often reserved for royalty, enhancing the tunic’s status as a high-value symbol of power and prestige.

One of the unique features of this tunic is its white, middle layer made of the mineral huntite, sandwiched between layers of royal purple cotton. The technique and materials used to create the tunic match descriptions of Persian royal garments, reinforcing its potential connection to Alexander, who, after conquering Persia, adopted many elements of Persian regalia and ritual.

Bartsiokas explains that after Alexander’s death in 323 BC, his tunic and other symbolic items—such as a golden oak wreath, a diadem, and a scepter, also found in Tomb II—may have been inherited by his half-brother, Philip III Arrhidaeus, who assumed a symbolic kingship over Macedonia. The researchers suggest this transfer of objects could have been part of the posthumous division of Alexander’s empire. The possibility of this royal tunic, known as a “sarapis,” being found in a Macedonian tomb, speaks to Alexander’s influence and his integration of Persian customs into Macedonian royalty.

Alexander the Great at the Battle of Issus (2nd century BC). Detail of a mosaic from the House of the Faun in Pompeii, Italy.

Alexander the Great at the Battle of Issus (2nd century BC). Detail of a mosaic from the House of the Faun in Pompeii, Italy. © Shutterstock

Alexander the Great at the Battle of Issus (2nd century BC). Detail of a mosaic from the House of the Faun in Pompeii, Italy.© Shutterstock

Cotton and Royal Purple: A Blend of Cultures

The use of cotton—almost unheard of in Macedonia during Alexander’s era—provides further insight into his Persian connections. Historical records suggest that Alexander introduced cotton to Greece following his conquest of Persia, which he absorbed into his own empire. The brilliant white middle layer of the garment, fashioned from the mineral huntite and surrounded by royal purple, further suggests that the garment symbolized Alexander’s fusion of Greek and Persian royal traditions. As Bartsiokas notes: “its combination with the royal purple was a symbol of royalty in Persia adopted by Alexander.”

The tunic, in its distinctive blend of materials, colors, and styles, may exemplify Alexander’s cultural adaptability. Cotton was a prized import, and the process of extracting purple dye from mollusks was both labor-intensive and costly, underscoring the garment’s exclusivity and value. Professor Susan Rotroff, an expert in ancient textiles, comments, “If the fabric is indeed cotton, it would be difficult to date it before Alexander’s time.”

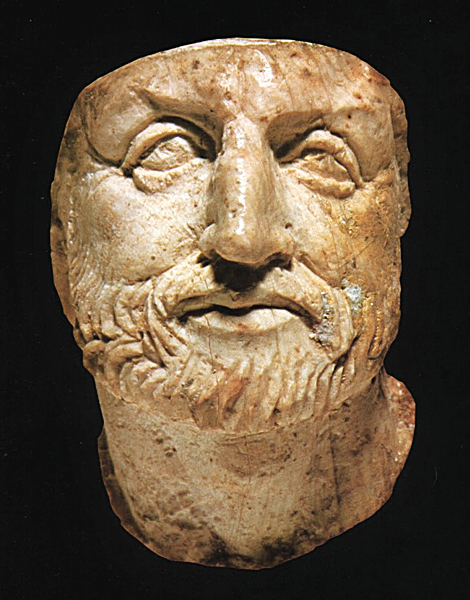

Head of Philip II, carved in ivory, from his tomb at Vergina (Museum of the Royal Tombs at Aigai-Vergina).

Head of Philip II, carved in ivory, from his tomb at Vergina (Museum of the Royal Tombs at Aigai-Vergina).

Head of Philip II, carved in ivory, from his tomb at Vergina (Museum of the Royal Tombs at Aigai-Vergina).

Head of Philip II, carved in ivory, from his tomb at Vergina (Museum of the Royal Tombs at Aigai-Vergina).

Coin of Philip III Arrhidaios. 323–317 BC.

Coin of Philip III Arrhidaios. 323–317 BC.

Coin of Philip III Arrhidaios. 323–317 BC.

Coin of Philip III Arrhidaios. 323–317 BC.

Controversy and Skepticism

Not all scholars are convinced by the evidence linking this tunic to Alexander. Hariclia Brecoulaki, a senior researcher at the National Hellenic Research Foundation’s Institute of Historical Research, suggests that the garment fragment may not be a tunic at all but rather a scarf or burial wrap. Critics also note that while Bartsiokas’s team used advanced analysis techniques, the garment itself has not yet been independently verified by other researchers.

Further complicating the narrative, some scholars argue that Tomb II may belong not to Alexander’s father, Philip II, but to Philip III Arrhidaeus, his half-brother. Forensic analysis of the skeletons in Tomb II reveals that one of the remains lacks the battle wounds known to have afflicted Philip II, suggesting instead the possibility of Philip III as the tomb’s occupant.

Nonetheless, other scholars, such as David Gill from the University of Kent’s Center for Heritage, support the findings, arguing that several artifacts in Tomb II likely post-date Philip II. “It is highly probable that this item belonged to Alexander,” Gill remarks, adding credence to Bartsiokas’s interpretation of the tunic as Alexander’s royal garment.

The Alexander Sarcophagus is a late 4th century BC Hellenistic stone sarcophagus from the Royal necropolis of Ayaa near Sidon, Lebanon. It is currently on display in the Istanbul Archaeology Museum.

The Alexander Sarcophagus is a late 4th century BC Hellenistic stone sarcophagus from the Royal necropolis of Ayaa near Sidon, Lebanon. It is currently on display in the Istanbul Archaeology Museum. © Shutterstock

The Alexander Sarcophagus is a late 4th century BC Hellenistic stone sarcophagus from the Royal necropolis of Ayaa near Sidon, Lebanon. It is currently on display in the Istanbul Archaeology Museum.© Shutterstock

The Broader Impact of the Discovery

If proven authentic, the tunic could serve as one of the precious few tangible links to Alexander himself, casting new light on the king’s legacy. Beyond its status as clothing, the sarapis symbolizes Alexander’s claims to divinity and Persian kingship. This chiton, worn only by royalty, connected Alexander to divine authority, a link that grew as he expanded his empire across Persia and Egypt. “This “chiton” was sacred (as Alexander was the son of Zeus-Amun with horns) and unique for him who was the King of Greece and Persia and Pharaoh of Egypt (i.e., a god), as no one else was allowed to wear it,” explains Bartsiokas. As a symbol of unity between cultures, the Persian sarapis would reflect Alexander’s ambition to merge Macedonian and Persian traditions.

This tunic joins a rich collection of artifacts that reflect Alexander’s enduring influence, from statues and coins bearing his image to the ancient cities he founded, such as Alexandria in Egypt and Kandahar in Afghanistan. Yet, Alexander’s own remains have never been conclusively identified, leaving historians to reconstruct his legacy through objects associated with him. Notable among these are the famed Alexander Sarcophagus, found near Sidon in Lebanon and now displayed at the Istanbul Archaeological Museum, and the intricate Alexander Mosaic in Pompeii, each providing glimpses into his celebrated life and achievements.

While his physical remains remain undiscovered, symbolic artifacts like the golden oak wreath—sacred to Zeus—and other significant relics found at Vergina convey the far-reaching scope of Alexander’s legacy. These items reveal a ruler whose ambition, divine lineage, and military prowess were revered and remembered long after his death, embodying the blend of Macedonian and Persian traditions that defined his empire.

Aigai became the seat of the royal court of the Argead dynasty, whose legendary ancestors included Hercules. Their greatest period of prosperity and political power came in the mid-4th century BC during the reign of king Philip II (359–336 BC), the father of Alexander the Great.

Aigai became the seat of the royal court of the Argead dynasty, whose legendary ancestors included Hercules. Their greatest period of prosperity and political power came in the mid-4th century BC during the reign of king Philip II (359–336 BC), the father of Alexander the Great. © Shutterstock

Aigai became the seat of the royal court of the Argead dynasty, whose legendary ancestors included Hercules. Their greatest period of prosperity and political power came in the mid-4th century BC during the reign of king Philip II (359–336 BC), the father of Alexander the Great.© Shutterstock

The Tomb’s Frieze: A Visual Link to Alexander

The fresco adorning Tomb II’s frieze bolsters the argument that Alexander may have been closely associated with these artifacts. The fresco depicts a royal lion hunt, an activity tied to valor and dominance. In the scene, a figure identified by Bartsiokas as Alexander wears a purple and white garment similar to the fragment found in the ossuary, embodying both royal and divine qualities. This visual connection strengthens the case for identifying the tunic as a garment associated with Alexander.

Ancient royal hunting imagery often symbolized kingship, valor, and control and dominance over nature. In this depiction, the heroic image of Alexander in his sarapis conveys a sense of divine power and authority, which his followers likely intended to convey through the symbolism in the tomb.

A Lasting Symbol of Alexander’s Influence

Should the tunic indeed be confirmed as Alexander’s, it represents a rare artifact directly linked to him. Alongside the golden wreath, diadem, and scepter, the chiton stands as a testament to Alexander’s unique legacy—a blend of Macedonian and Persian cultures that still fascinates scholars and the public alike. Through this ancient fabric, Alexander’s story comes to life, allowing us to glimpse the grandeur of a ruler who reshaped the ancient world.

Alexander’s military campaigns stretched across continents, from Greece to the Indus Valley, where he embraced local customs and unified diverse cultures under his rule. This chiton, found in Vergina, not only offers a rare physical link to the actual individual but underscores the allure of Alexander’s story, one that continues to captivate and intrigue. As research progresses, this fabric may reveal more about the lives and legacies of the people interred in Vergina, adding another chapter to the enduring saga of Alexander the Great.

1 month ago

11

1 month ago

11

Greek (GR) ·

Greek (GR) ·  English (US) ·

English (US) ·