How the cargo of a prehistoric shipwreck beneath the Argosaronic Gulf revealed a sophisticated maritime trade network in the Early Bronze Age Aegean.

Some four thousand years ago, a small merchant vessel slipped quietly through the calm, sapphire waters of the Argosaronic Gulf, her low wooden hull laden with cargo. She had likely departed from a coastal settlement in the Argolid, her crew – no more than four or five mariners – navigating by sightlines and seasonal patterns: the shapes of hills and islands, the direction of cloud-banking, the feel of wind and current beneath the sail.

In her hold were hundreds of ceramic vessels – storage jars, sauceboats, cooking pots, and tableware – carefully packed for transport, bound for coastal villages or trading outposts along the southern edge of the Myrtoan Sea. This was no exploratory journey, but a regular voyage across known waters.

This was the Early Bronze Age, a time before the rise of Mycenae and before the sprawling Minoan palaces of Knossos and Phaistos reached their height. Writing had not yet come to Greece. But seaborne commerce was already shaping the Aegean. The ship’s route lay along an emerging web of maritime trade that linked South Euboea with the gulfs of the Argolid and Saronic – an early network of direct exchange that marked a shift from down-the-line transmission to something more intentional, more connected.

View from Hydra across the Argosaronic Gulf, with Dokos to the left and the Peloponnese in the distance. Inhabited since at least 6000 BC, Dokos was once a strategic node in early Aegean maritime networks.

View from Hydra across the Argosaronic Gulf, with Dokos to the left and the Peloponnese in the distance. Inhabited since at least 6000 BC, Dokos was once a strategic node in early Aegean maritime networks. © Shutterstock

View from Hydra across the Argosaronic Gulf, with Dokos to the left and the Peloponnese in the distance. Inhabited since at least 6000 BC, Dokos was once a strategic node in early Aegean maritime networks.© Shutterstock

Somewhere off the rocky shore of the island now called Dokos, the voyage came to a sudden, catastrophic end. Perhaps a squall caught them in open water, or a misjudged turn of the steering oar brought them too close to the coast. The vessel foundered and sank, and her crew were lost or scattered. Over time, the sea took the timbers, but the cargo remained, resting undisturbed on the seabed for more than four millennia.

Today, the water above that fateful spot barely hints at the archaeological marvel below. Discovered in 1975 and excavated in the late 1980s, the Dokos Shipwreck is now recognized as the oldest known underwater shipwreck in the world. It offers an extraordinary glimpse into the nascent world of Aegean maritime trade – a story not drawn from epic poetry or monumental buildings, but from a humble cargo of ceramic ware.

Peter Throckmorton and his team encountered a wide scatter of ceramic vessels strewn across the rocky seabed – similar to the scene pictured here.

Peter Throckmorton and his team encountered a wide scatter of ceramic vessels strewn across the rocky seabed – similar to the scene pictured here. © Shutterstock

Peter Throckmorton and his team encountered a wide scatter of ceramic vessels strewn across the rocky seabed – similar to the scene pictured here.© Shutterstock

A Scatter in the Deep

For more than forty centuries, the wreck site near Skindos Bay lay undisturbed in the shallow blue waters of the Hydra Strait, between the island of Dokos and the eastern Peloponnese. It wasn’t until August 23, 1975, that the stillness was broken.

Peter Throckmorton (1928–1990), a pioneering American underwater archaeologist, best known for his work on the Late Bronze Age Cape Gelidonya wreck in the 1960s, was conducting a seabed survey off the uninhabited islet – known in antiquity as “Aperopia.” As Throckmorton and his team dived to depths of 15 to 30 meters, they encountered an extraordinary sight: a large scatter of ceramic vessels spread across the rocky seabed. There was no hull, no timbers, no skeletal remains of the ship itself – but the pattern was unmistakable. A merchant ship had sunk here.

What they found were hundreds of clay vessels, many partially buried in silt and fused together by marine concretions: amphorae, wide-mouthed jars, sauceboats, bowls, braziers, baking trays, and smaller containers like “askoi.” Their forms didn’t match the known typologies of Classical or even later Bronze Age material. When ceramic specialists were consulted, the results were astonishing: the cargo dated to the Early Helladic II period, around 2200 BC – making this the oldest known underwater shipwreck ever discovered.

Mapping the Site

At the time, maritime archaeology in Greece was still in its infancy, and the discovery offered a glimpse into a world centuries before the height of the Minoan thalassocracy, revealing that organized maritime trade was already well underway in the Aegean more than four millennia ago.

More than a decade later, between 1989 and 1992, a full-scale excavation was undertaken by the Hellenic Institute of Marine Archaeology (HIMA) under the direction of Dr. George Papathanasopoulos, one of Greece’s leading archaeologists. His team faced a challenge: the seabed was uneven and rocky, the cargo dispersed across a broad area, and there were no structural remains to anchor the excavation grid.

To overcome this, HIMA deployed a then-revolutionary geospatial tool: SHARPS – the Sonic High Accuracy Ranging and Positioning System. Using a network of acoustic transmitters and underwater beacons, divers were able to record the exact position of each artifact with precision, bringing the wreck site to life in scaled maps. For the first time in Greek waters, an ancient shipwreck was being recorded to the same exacting methodological standards as a land excavation.

Divers later described the site as “a submerged museum,” where clusters of ceramic vessels emerged from the silt like carefully packed cargo, undisturbed for four thousand years.

Over the course of four seasons, the team recovered more than 15,000 pottery sherds and complete vessels, each one logged, mapped, and lifted with painstaking care. Alongside the ceramics were millstones, two lead ingots (from Lavrion in Attica?), and two stone anchors found some 40 metres from the main scatter – strong evidence that this had been a functioning merchant vessel engaged in regional trade.

Once raised, the cargo was transported to the Spetses Museum for conservation and study, where it continues to offer valuable insight into the economic networks, craft practices, and maritime lifeways of the Early Bronze Age Aegean.

Underwater archaeology in Greece was still in its infancy when the Dokos shipwreck was excavated in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Underwater archaeology in Greece was still in its infancy when the Dokos shipwreck was excavated in the late 1980s and early 1990s. © Shutterstock

Underwater archaeology in Greece was still in its infancy when the Dokos shipwreck was excavated in the late 1980s and early 1990s.© Shutterstock

Spouted bowls (“sauceboats”) from the Early Helladic II period (c. 2800–2300 BC), excavated at Askitario. Vessels of this type were among those recovered from the Dokos shipwreck.

Spouted bowls (“sauceboats”) from the Early Helladic II period (c. 2800–2300 BC), excavated at Askitario. Vessels of this type were among those recovered from the Dokos shipwreck.

Spouted bowls (“sauceboats”) from the Early Helladic II period (c. 2800–2300 BC), excavated at Askitario. Vessels of this type were among those recovered from the Dokos shipwreck.

Spouted bowls (“sauceboats”) from the Early Helladic II period (c. 2800–2300 BC), excavated at Askitario. Vessels of this type were among those recovered from the Dokos shipwreck.

Ceramics, Seafaring, and Traces of an Early Trade Route

At the heart of the Dokos wreck lies its cargo: an extraordinary collection of ceramic vessels that offers a precious glimpse into the domestic, economic, and artistic life of Early Helladic Greece. With more than 500 complete or reconstructable pots and over 15,000 sherds, the site represents one of the largest closed groups of Early Helladic II pottery ever discovered.

The diversity is striking. Amphorae, wide-mouthed jars, sauceboats, bowls, braziers, baking trays, and small ladle jars or “askoi” were recovered from the seabed, many still clustered together as they would have been packed aboard the vessel. Most were utilitarian – meant for storing, cooking, and serving food – but some, like the elegantly curved sauceboats with long spouts and offset handles, may have had ceremonial or elite domestic functions. Their stylistic affinities with ceramics from Askitario in Attica, Lerna in the Argolid, and several Cycladic sites suggest shared manufacturing practices and the circulation of common vessel types across the Aegean.

But perhaps most intriguing of all is the pottery’s method of manufacture. These vessels were not made on a wheel, which had not yet become common practice in the Aegean. Instead, they were shaped entirely by hand – coiled, smoothed, and carefully formed, then often burnished or coated with a slip before firing. Decoration was minimal, if present at all. Yet their apparent simplicity masks a high degree of technical control. The uniformity in shape, proportion, and finish suggests a level of standardization difficult to achieve without specialized training. This was not rustic village ware; it was precision-crafted, almost certainly in organized workshops, most likely located in the Argolid. These pots were made not for household use alone, but for distribution on a regional scale.

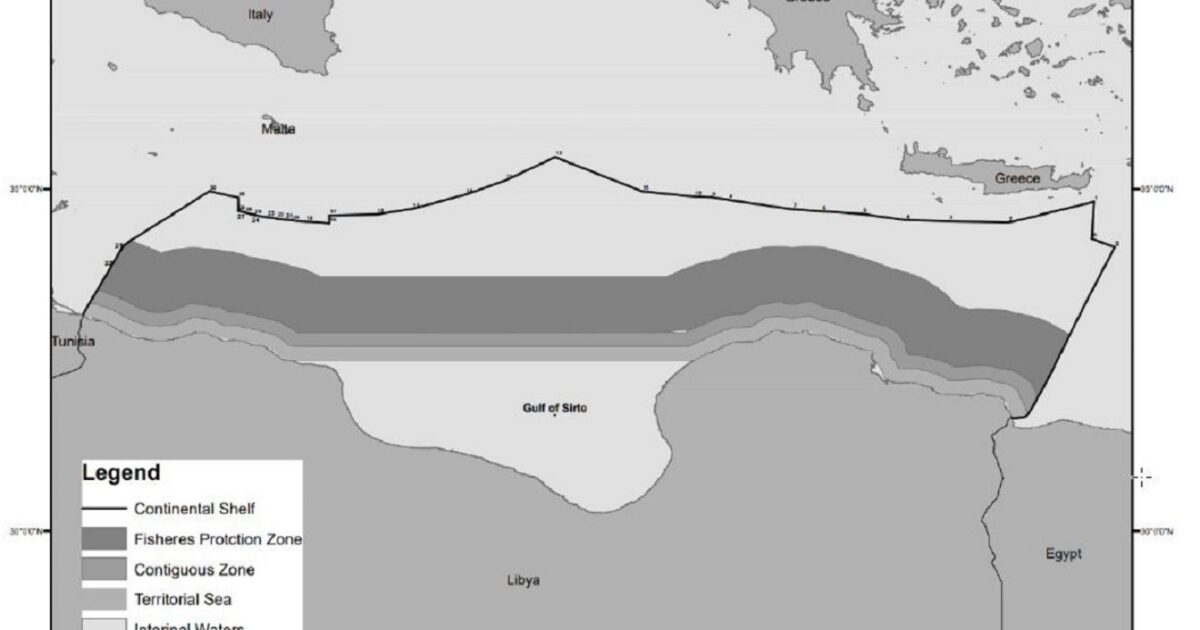

The inclusion of millstones and lead ingots among the cargo reinforces the interpretation of the vessel as a merchant ship, its wares bound for smaller settlements or coastal communities that lacked their own ceramic industries. This was not a personal haul, but a commercial payload – evidence that, even before the palatial economies of the second millennium BC, the Aegean was already a well-trafficked trade corridor.

The so-called “frying pan” from Syros (NAMA 4974), featuring a stylized ship motif – one of the few surviving depictions of Early Bronze Age seacraft. Now on display at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens.

The so-called “frying pan” from Syros (NAMA 4974), featuring a stylized ship motif – one of the few surviving depictions of Early Bronze Age seacraft. Now on display at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens.

The so-called “frying pan” from Syros (NAMA 4974), featuring a stylized ship motif – one of the few surviving depictions of Early Bronze Age seacraft. Now on display at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens.

The so-called “frying pan” from Syros (NAMA 4974), featuring a stylized ship motif – one of the few surviving depictions of Early Bronze Age seacraft. Now on display at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens.

As for the ship itself, it has long since vanished. The wooden hull, probably constructed from softwoods like pine or fir, dissolved in the seawater centuries ago. Only the cargo and a set of stone anchors, found some 40 meters from the main scatter, remain. Yet its outline can be inferred: a modest-sized vessel, likely crewed by four or five people. Its propulsion system is unknown, but iconography from the Early Cycladic period – particularly on enigmatic ceramic “frying pan” vessels – depicts long, narrow hulls, some with rows of oars and possible rigging. This has led some scholars to suggest that vessels of this period were either oared canoes or hybrid craft capable of sail.

The ship likely departed from the Argolid – perhaps near Lerna, a major Early Bronze Age center – and was headed east across the Saronic Gulf, possibly continuing toward Syros, Euboea, or the western Cyclades. The vessel’s contents mirror pottery found at these sites, suggesting it was part of an established maritime circuit linking the central mainland with Aegean island communities.

We do not know what brought the voyage to an end – an unexpected squall, a navigational miscalculation, a poorly timed approach to a rocky coast. But the wreck offers more than a snapshot of loss. It illuminates a world of maritime connectivity: a network of trade, craftsmanship, and early navigation that prefigured the Aegean’s later palatial splendors.

The Spetses Museum, where many of the artifacts from the Dokos shipwreck are conserved and displayed. The museum’s collections span over 4,000 years of the island’s cultural history.

The Spetses Museum, where many of the artifacts from the Dokos shipwreck are conserved and displayed. The museum’s collections span over 4,000 years of the island’s cultural history. © Shutterstock

The Spetses Museum, where many of the artifacts from the Dokos shipwreck are conserved and displayed. The museum’s collections span over 4,000 years of the island’s cultural history.© Shutterstock

If You Go

While the wreck site itself is protected and off-limits to divers, the island of Dokos remains accessible by boat from Hydra or Ermioni. It is uninhabited today, but from its rocky slopes, the Argosaronic Gulf unfolds in all directions – still, blue, and seemingly empty; its surface betraying little of the lives once lost beneath.

These were not the first seafarers in Greek waters – but they were among the earliest whose voyage left such a vivid archaeological trace.

For a closer connection to the wreck’s story, visitors can explore the Spetses Museum, where many of the recovered artifacts are now housed. There, amid burnished bowls and slip-coated sauceboats, the ship’s final journey is made tangible – its story carried not in myth, but in clay.

1 month ago

67

1 month ago

67

Greek (GR) ·

Greek (GR) ·  English (US) ·

English (US) ·